A few months ago, someone online made the statement that there were few (popular) characters to inspire women in a virtuous life, while there were several for men, which naturally provoked a response.

This became a whole conversation with clarification and additions made by both sides. I don’t wish to recap that whole discussion, but suffice it to say, it inspired this post and made me think about women in literature who present to me an image of what it means to live a virtuous life.

I was a little hesitant to write this, since I didn’t want to imply that women can only learn from female characters and that men can only learn from male characters. If that were true, I’d have to reject many of my favorite characters on the grounds of them being male, something I’m not at all inclined to do. (For examples of men learning from female characters, in particular those of Jane Austen, see this book, this essay, and this short story1.)

All the same, I did think there was something here worth saying, by someone anyway. And I have written before about men in literature, so perhaps this would be an unlikely accusation. Online, we tend to have the stereotypes of “girlboss” and “tradwife” presented as though these were the only options for women. Either autonomy at all costs and without moral consideration or else meek subservience and mindlessness, as each might caricature each other (and as this is online, there’s more caricature than anything else).

But looking at both history and literature, we find a much more whole picture. It’s easy to be selective and only pick out what fits our own particular ideology, making it look like everyone was thinking along our modern fault lines back to Cain and Abel, but as it happens, the people of the past had their own ideas and debates. These have fed into our own, as the river of the past always does, but that does not mean you can discover the shape of the source spring from the lake below.

We have thousands of years of discussion, a continuous back and forth across the ages. Where one sole voice would err to one side, another speaks as his opposite, making a whole picture. This wholeness is what delights and astonishes me.

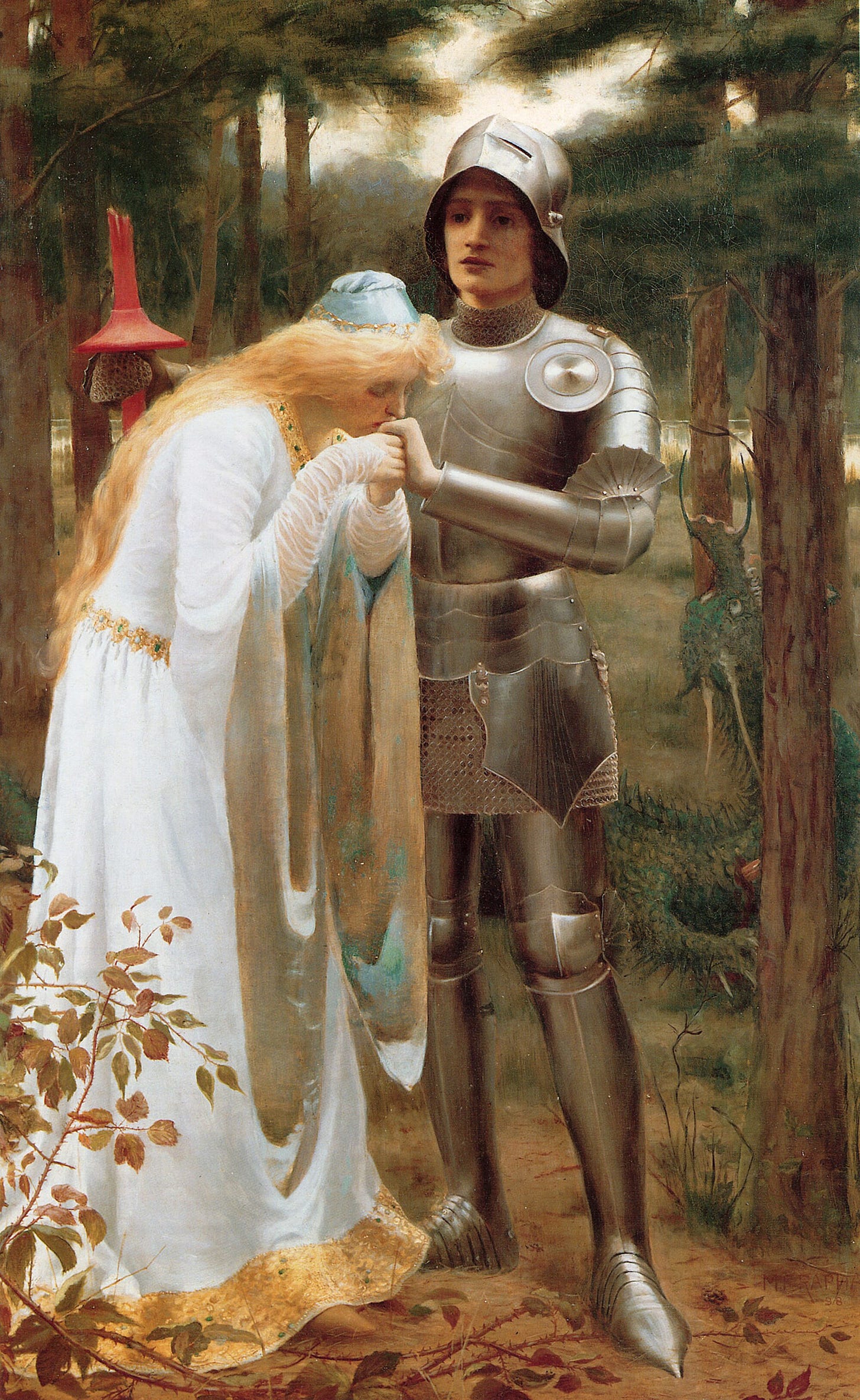

“Britomart and Amoret” by Mary M. Raphael (1898). “Princess Britomart, disguised as a knight, fulfilling a vow to her absent lover, rescues the Lady Amoret from durance vile by slaying the monster Busyran.” - Spenser's Faerie Queene, Book IV. Canto 1. I have yet to read Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene, but I have the feeling that once I do, I might have something more to say on this subject.

One story that illuminates this for me is The Lord of the Rings. Galadriel is a bearer of one of the Rings of Power, member of the White Council, and Sauron’s nearest equal among the Children of Ilúvatar. She is the Lady of Light, giver of gifts, and the sight of her is enough to make Gimli the dwarf her devoted servant to the end of his days. She is Queen and Mother, a figure of striking beauty and power.

Next is her granddaughter, Arwen Undómiel, destined to trade immortality for mortal love and crown. She is less visible at first reading, as much of her story takes places outside of the fellowship’s quest. Her role is one familiar from fairy tale and myth: the princess, Guide and Beloved. In the appendices to The Return of the King, Arwen plays an almost alchemical role in a young Aragorn’s life. It is at the sight of her and the love born in that moment that he becomes a man, setting out from his foster-father’s house, finding a mentor in Gandalf, and developing the character and skills he will someday need. Even in The Fellowship of the Ring, this is glimpsed; it is in her presence that Aragorn first appears as an heir of kings before the eyes of the hobbits. Her beauty is far more than well-formed features; it is her whole being. She reflects something of what beauty means, of which the physical is only the most obvious. That beauty is what calls a young Aragorn into manhood, watches over him in his long years of wandering, and guides like the Evenstar for which she is named.

Lastly is Éowyn, shieldmaiden of Rohan. Her heroic moment at the Battle of Plennor Fields before the walls of Gondor is iconic, in the books and movies alike. But that moment is only one in her journey from despair to hope, from a suicidal desire to regain her people’s lost honor in glorious death to a new purpose found in love and healing. Her climax is not the battlefield, but in the Houses of Healing, when her heart is changed and it is said of her, “Here is the Lady Éowyn of Rohan, and now she is healed.”

The weddings with which The Lord of the Rings ends, from the mythic marriage of Aragorn and Arwen down to the humble union of Sam and Rosie, are a sign of the healing of the world. No more will people live in fear, fighting lonely battles at the edge of the world, but now they will marry and have children and grow gardens. The world is set right again.

In these women, and others from Middle Earth that I don't have the space to discuss, we see warriors and wives, queens and healers. They’re extraordinary, often archetypal, figures who form a part of our modern mythology. The women of Middle Earth aren’t wilting and passive, but neither are they so-called “girlbosses.” They possess both strength and femininity, power and beauty.

But as I said, those are archetypes. Wonderful to have in myth, rich for contemplation, and utterly important for our imaginations, but perhaps distant to our lives at times. I do believe myth has a practical bearing on our day-to-day lives, and perhaps will explicate that further someday. However, sometimes we want to see what this means lived out in ordinary lives.

That will be the subject for next week.

A Jane Austen Education by William Deresiewicz; “On Jane Austen and the General Election” by G. K. Chesterton; and “The Janeites” by Rudyard Kipling, respectively. The last two are public domain and available for free online, though not the first.

Very good. Reject reductionisms.